Clint Eastwood has been making movies for over sixty years, and in his 94th year we see the release of what may be his best work. It is certainly up there with ‘Million Dollar Baby’, ‘Mystic River’ and even ‘Unforgiven’ for the way that it seeks to understand the complexities and muddied waters of the US justice system, with an intensely personal angle. There are the usual tropes of the family outsider – richly embodied in Eastwood’s own performance as William Munny in ‘Unforgiven’, a devout family man who has to question his own loyalty to family when he needs to take a stand against an injustice, the net result of which is that he self-alienates himself from any kind of communal or familial relationship. It raises the age old question of whether one needs to step outside of the law in order to fulfil the law, but at a great personal cost.

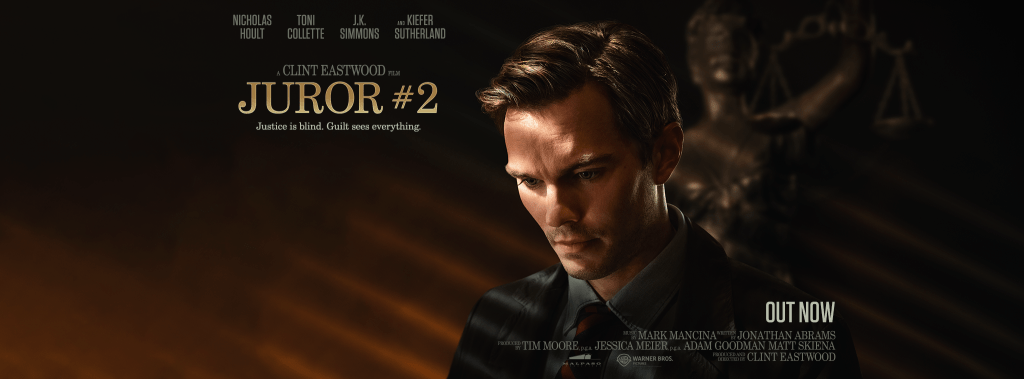

The context of ‘Juror #2’ is at first reminiscent of ’12 Angry Men’ with its delineation of how a case that appears to be cut and dry, with a jury deliberation over what looks like the inescapable guilt of the accused, leading to a very different sort of investigation. In this case, one of the jurors has a relationship to the case which they only discover once the trial has commenced, and while this is the sort of potboiler legal drama that would not look out of place in a John Grisham adaptation, Eastwood is unafraid to use the twisty legal thriller trope as a hook on which he can reel in the audience to question their own prejudices and need for closure and certainty, not least when it comes to the way the demand for retribution or vengeance may itself come up against other sacred structures relating to compassion, family and love.

Is the need to kill a stronger emotion or sacred form than the arguably harder facility of knowing how to love one’s enemy and to acknowledge that people’s motivations or actions are rarely black and white and that the need to apportion blame or administer punishment may say as much about our own frailties and doubts than it does about the demonic Other who we might be happy to be sacrificed, and receive expiation, for our own sins.

‘Juror #2’ does an incisive job of what in lesser hands would be a hackneyed, simplistic presentation of a string of implausible coincidences, in which a juror is torn between the demands of family (his wife is about to give birth and the trial on which he is serving is unlikely to have resolved by her due date) and justice (he is in a minority on the jury because he knows that the accused didn’t commit the crime), and in siding with one over the other he is liable to be doomed.

Other jurors are keen to make a swift decision so that they can return to their families, but Justin (Nicholas Hoult) has to find ways of protecting himself and being there for his family while trying to save the accused from a wrongful incarceration (here, there are shades of Eastwood’s thriller ‘True Crime’ from 1998) without implicating himself in the judicial process. Eastwood has conventionally resolved arguments in his films with a gun, as we saw with the ‘Dirty Harry’ films in the 70s and 80s, but here an off-screen Eastwood is in fully self-reflective mode, cleverly not showing us the jurors’ final deliberations, leaving us to find out only when the verdict is announced in court whether the accused is guilty or not guilty.

And the ending is a wonderfully ambiguous, even ambivalent, one which just about redeems for the ‘way of the gun’ in the mode of Detective Harry Callahan over a half century earlier. Critically, this is a neat way for Eastwood to bow out, with redemption, if it comes, being actualized via reason, intelligence and analysis instead of a bullet. It’s an assured, masterful film, and arguably Eastwood’s greatest.

Leave a comment