‘Howards End’ is an elegiac and sharply subversive heritage drama, with this adaptation of Forster’s seminal novel from 1910 containing both the opulence we come to expect from period dramas while also comprising a damning indictment of the Edwardian English class system. It often takes an outsider to supply the best sort of critique of a culture, as we saw with John Schlesinger’s disease-stricken variation on the American Dream in ‘Midnight Cowboy’. Here, American director James Ivory offers us a critique of the way the insularity and inward-looking sensibilities of different variations of upward mobility among the upper middle classes plays out among those not in their social circles, for whom a casual put down or a piece of badly framed advice can lead to calamitous consequences, with a vacuum of personal or moral responsibility the springboard for this dissection of the porous boundaries that lie between virtue and vice.

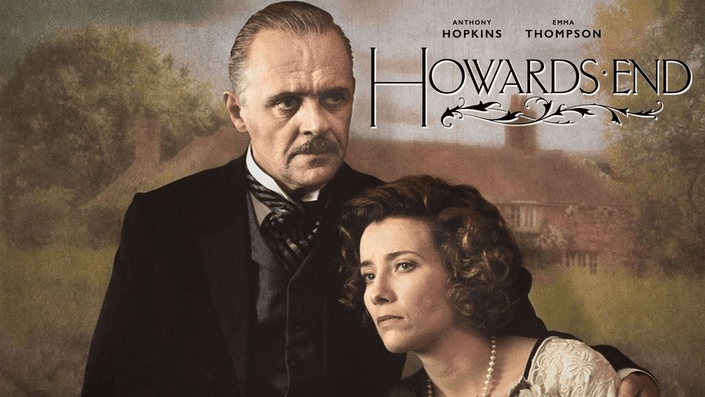

The film is redolent in questions of the extent to which we are defined by our privileges and whether those higher placed in the social hierarchy are more able to exonerate themselves from their transgressions. Two strong, independently minded, philanthropically-orientated sisters, played by Helena Bonham Carter and (Oscar-winning) Emma Thompson, have their principles thrown into question by their respective relationships to men who sit on opposite ends of the socioeconomic hierarchy. The place of both women and the working class is shifting, albeit slowly, in this tale of class divisions, though as a film it doesn’t have quite the same sense of clarity, structure or emotional heft as that between Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson in the following year’s ‘The Remains of the Day’.

Good intentions here turn into economic and personal disaster for the Basts, at the lower end of the social mix, and ‘Howards End’ is a brilliant film for precisely the way that it both nostalgically evokes a bygone era while also shocking us with its delineation of sacrificial victims and comeuppances (or the lack thereof) and the crimes that go unpaid and unpunished. Doing justice to a sprawling novel while adhering to the constraints and conventions of cinema is not always accomplished well, but Ivory uses black outs to end scenes, often seemingly mid way, and will then cut to another scene which acts as counterpoint, and this gives ‘Howards End’ a sense of rapidity and depth which would not have worked in lesser hands.

Leave a comment