There is a deep poignancy to ‘Vertigo’ which was the first of three Hitchcock classics to be released in consecutive years – the others being 1959’s ‘North By Northwest’ and 1960’s ‘Psycho’ – all of which have entered the canon not just as Hitchcock’s top films but the greatest movies of all time. James Stewart is the police detective whose vertigo inadvertently leads to the death of one of his colleagues while on a rooftop chase, and when an old schoolfriend approaches him about tailing his wife, who seems to be possessed by a ghost from the previous century, Stewart’s Scottie is at first reluctant to investigate, only to find himself obsessed with the woman whose graceful and enigmatic movements across San Francisco Bay lead Scottie to abandon any sense of reason.

Madeleine (Kim Novak) appears to be sleepwalking, as she channels a woman from the middle of the nineteenth century whose painting hangs in a gallery to which she visits every day, and who died at the same age that Madeleine is now, and after Scottie manages to prevent Madeleine from drowning in the Bay he fails to prevent her from a second suicide attempt, this time involving a bell tower, due to his vertigo. When a shopgirl, Judy, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Madeleine, then appears in his life some years later, she appears to both work as a palliative for Scottie, who by this stage is in a psychologically ruptured state on account of witnessing but being unable to prevent two deaths involving falling, while he is also vulnerable to the possibility of there being a third death, with the forces of destiny conspiring to draw Scottie into the abyss.

The male gaze is all-encompassing here except when at one crucial point, before the end, Judy herself mentally revisits the events that led Scottie to her door, and we start to see that he is being exploited on account of his tortured mental state, a pawn in a complex game where he cannot not act in the way that he does, and where Madeleine/Judy both draw him towards them, fully knowing about and exploiting his disability, while at the same time pushing him away. Freudian themes relating to the unconscious and dreams are here fused with Catholic guilt as Scottie even tries to extricate himself from the nightmare, once he realizes he is being conned, only for the film to take us somewhere he could not himself have anticipated. The harder he climbs, the faster he plummets.

Although this is technically a tale of murder and betrayal, we see it through the lens of a psychologically traumatized hero, rendering ‘Vertigo’ a tale not so much of ‘whodunnit’ as focusing on the impact of the puzzle on the life of a man unwittingly used as a pawn, whose last act realization that he is being gaslighted sadly fails to alter the premeditated, predestined contours of his descent, in line with the trappings of a film noir tragic drama.

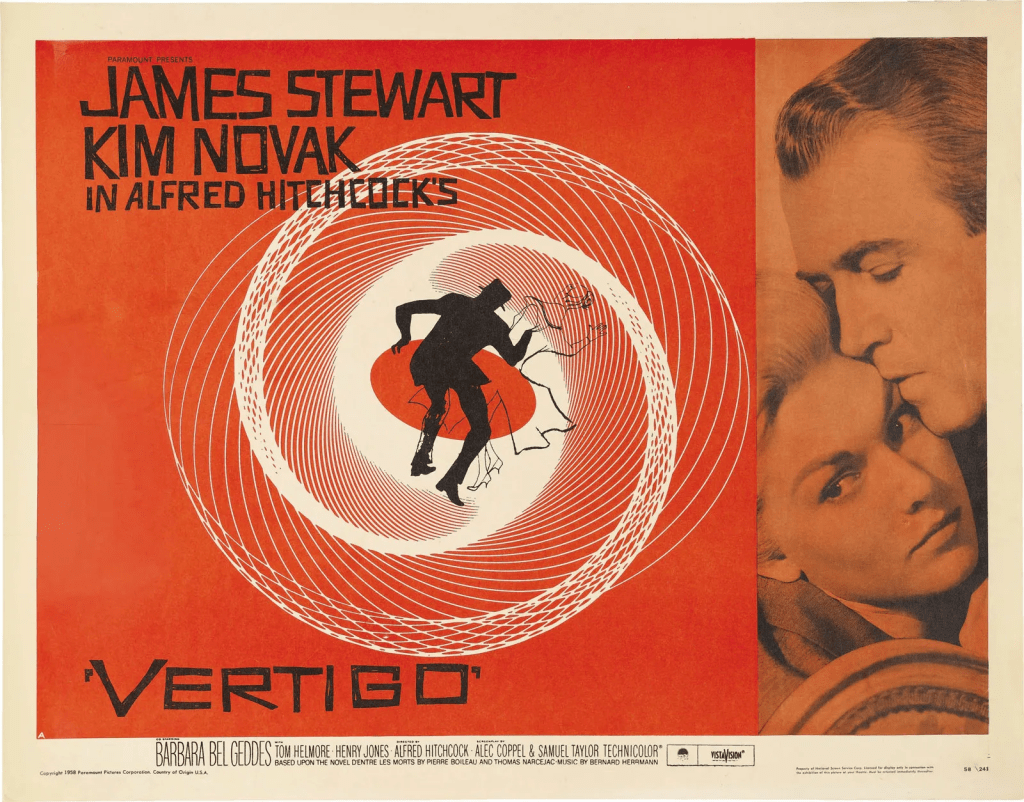

This is indeed a tale of Dante’s Inferno reconstituted as a modern psychological noir fable, whose slow pace is the polar opposite to that of the following year’s ‘North By Northwest’, but it is gripping, with a spectacular score from Bernard Herrmann and title design from Saul Bass and revolutionary use of camerawork, including the simultaneous zoom forward and track back camerawork which serves to augment the dizzying, suspense-laden mystery which, even if you have watched it before, never fails to pull you back in.

Leave a comment