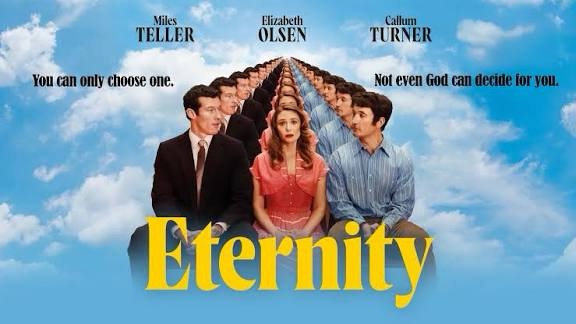

‘Eternity’ is a romantic comedy with a beautifully philosophical twist – one that takes place not on Earth, but in a heavenly way-station somewhere between life and whatever comes next. It’s a film very much in the tradition of ‘Defending Your Life’ with Meryl Streep and Albert Brooks, or ‘Chances Are’ with Cybill Shepherd and Robert Downey Jr. – stories where love continues into the afterlife, but the choices become even more complicated.

Here, our central character is a woman in her eighties who has lived a full sixty-five years with her husband. But she also once had a youthful marriage – brief but passionate – to a young soldier who died in the Korean War. When she dies, she arrives in this celestial transit lounge and discovers both husbands waiting for her… each convinced they are the love she should choose for eternity.

That dilemma opens up a world of theological and philosophical playfulness. St. Augustine once suggested that in the resurrection we appear at our prime – around 30, Jesus’ age when he was resurrected – and the film adopts that idea very literally. All the souls here revert to the point when they felt most themselves. For some that’s youth, for others a different chapter entirely. One older woman, for example, finally gets the chance to live a fulfilled queer life after decades of suppressing her identity in a straight marriage. This feels very empowering.

The afterlife itself is run like a cosmic travel agency: choose your paradise – a cabin in the woods, Studio 54, France in the 60s – and climb aboard a literal train to your eternity. But once you choose, that’s it. No returns, no do-overs. And that creates the central emotional tension: what if the love of one chapter is no longer the love you want forever?

It’s also an afterlife without angels or God stepping in. Instead, administrative figures – including Da’Vine Joy Randolph in a witty role – do the paperwork, explain the rules, and try to help these souls navigate desire and destiny. It’s bureaucracy meets metaphysics – very ‘Heaven Can Wait’ – where transcendence isn’t about divine glory but about human relationship.

The film even touches gently on ideas from theologians like John Hick and H.H. Price – suggesting an afterlife shaped by personal imagination, community, and unfinished business. There’s no celestial surveillance or omniscience; if someone breaks the rules, the “afterlife police” physically run from room to room to find them. It’s Earth… but without death as a consequence. Smokers can smoke forever; their lungs won’t give out a second time.

What the film ultimately explores is whether love is defined by longevity or intensity: Do you choose the person who shaped your life? Or the one who might have changed it if they’d lived longer?

It’s a kind of supernatural ‘Sliding Doors’, inviting audiences to quietly ponder whether they themselves are with the right person – not just for now, but for eternity.

If the film falters anywhere, it’s in the slightly limiting assumption that a fulfilled eternity must be romantic. The teasing suggestion that you could choose independence is only temporary – the narrative always pushes us back toward choosing Husband A or Husband B.

But it’s a warm, funny, quietly profound film – one that blends celestial comedy with centuries of human wondering about who we are, who we love, and whether eternity is simply the life we know… turned inside out.

Leave a comment