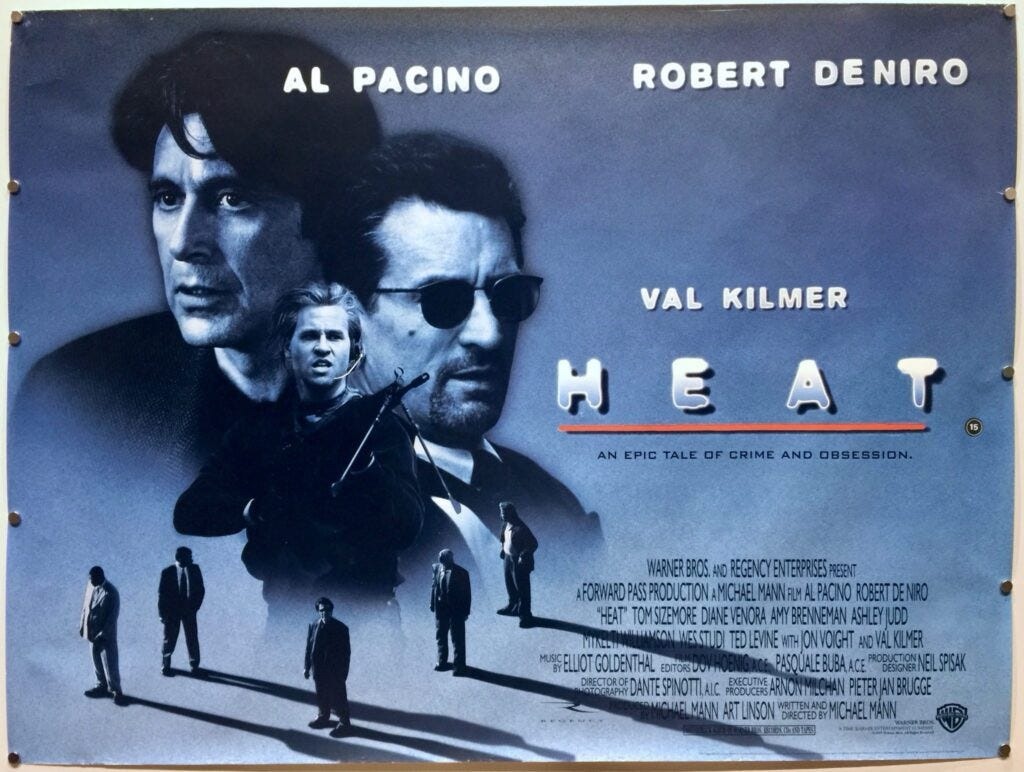

Michael Mann’s ‘Heat’ remains one of the defining crime epics of modern cinema – a three-hour duel of loyalty, identity, and professional obsession between two men on opposite sides of the law who, in truth, might be the only people who truly understand each other.

Robert De Niro plays Neil McCauley, a master thief whose life is governed by precision and discipline. His rule is simple: never get attached to anything you can’t walk away from in 30 seconds flat. His world is transactional, pared down – and when one member of his crew impulsively kills witnesses during a robbery, McCauley knows he must eliminate him. Not out of bloodlust – but because this is the code that keeps the whole precarious life afloat.

And Mann is careful not to glamorize these criminals. They are professionals who also have families, vulnerabilities – and the very human desire to escape the void that defines them.

On the other side is Al Pacino as Vincent Hanna – a brilliant but broken L.A. detective who throws every ounce of himself into the chase. His home life is in pieces: a marriage strained to snapping point, and a troubled stepdaughter whose pain becomes a devastating subplot. He’s a good man, but with nothing left for the everyday world – because the job consumes him.

Pacino and De Niro are like mirror images: different roles, same compulsions. They can’t be anything other than what they are.

Mann captures that connection famously in their first ever shared scene together – a quiet coffee-shop conversation. No gunplay, no theatrics. Just two men who could almost be friends if life hadn’t put them on opposing trajectories. It’s as if they both know that the chase is inevitable – and that only one will walk away.

Yes, ‘Heat’ could easily have been a brisk 100-minute heist thriller – but the reason it remains a masterpiece is the depth of character Mann excavates in the stillness between the action. Everyday life – relationships, routine, compromise – is precisely what these men cannot do. The moral vacuum at the core of their lives becomes the emotional engine of the story.

Visually, it’s a version of Los Angeles stripped of glamour – a perpetual blue dusk that mirrors the malaise and existential bankruptcy at the heart of the city. When violence does erupt – in those thunderous street shootouts and the final airport runway confrontation – it feels like the unavoidable consequence of men who live without a safety net.

By the end, when McCauley and Hanna face one another on the tarmac, jets roaring overhead, it’s not just good vs. evil – it’s two professionals completing the logic of their lives.

‘Heat’ is pure cat-and-mouse, but with a haunting question beneath every bullet: What if the thing you’re best at is also the thing that keeps you alone?

Leave a comment