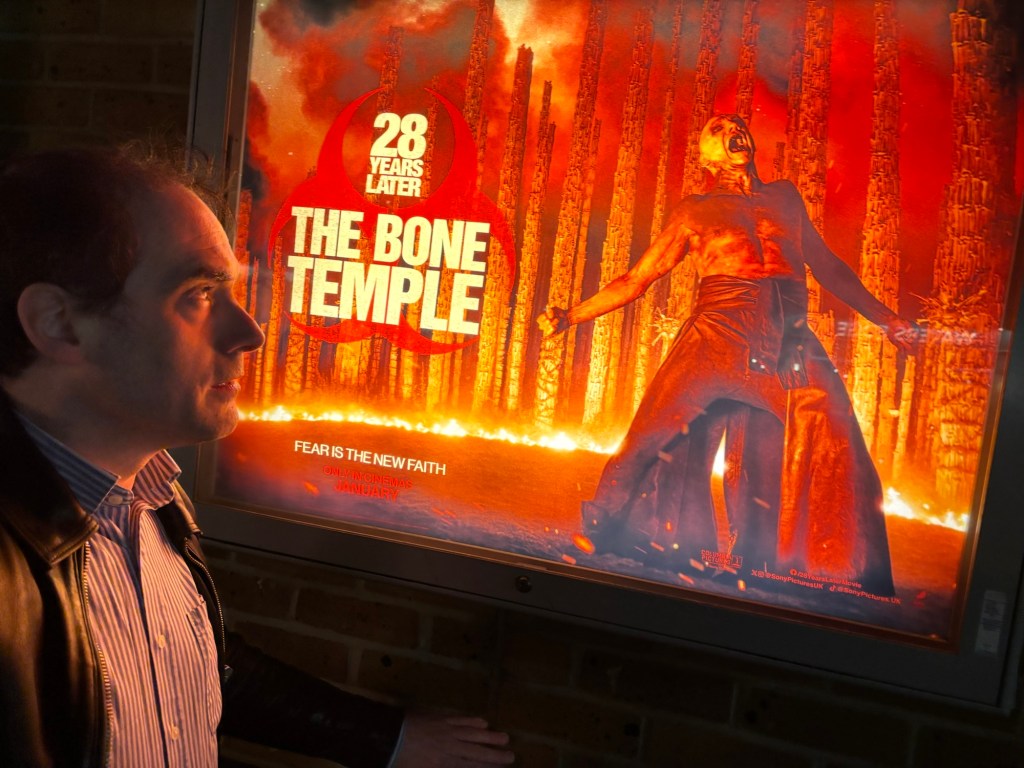

‘28 Years Later: The Bone Temple’ has a stark good-versus-evil architecture running through it. Danny Boyle didn’t direct this instalment, but it still feels like a throwback to his original vision in 2002’s ‘28 Days Later’: brutal, propulsive, and steeped in moral dread. If 2025’s ‘28 Years Later’ played as a Brexit parable – the idea of shielding yourself off from the world, treating the outside as a contaminated mass, and standing your ground against ‘polluted foreigners’ – then ‘The Bone Temple’ is even harsher, because it suggests that the infected aren’t the only threat. Evil among the non-infected may be just as bad, if not worse.

The film is punishing to watch. Twelve-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams) is rescued from the infected by a tracksuit-wearing gang of warriors who call themselves the Jimmies – explicitly modelled on Jimmy Savile. There’s no comedy in this, no wink: they’re closer to Alex and the Droogs in ‘A Clockwork Orange’, only stripped of any style that might soften the ugliness. Spike has to fight for his life, and the film makes you sit with the cruelty of it. He’s forced into a grim logic where he either kills a gang member or dies himself, and all the while their leader – Lord Sir Jimmy Crystal, who presents himself as a kind of ‘son of Satan’ – watches on like an emperor in an arena. It’s ‘Gladiator’ energy: ritualized violence, dominance as theatre, cruelty as entertainment.

At the other end of the spectrum is Ralph Fiennes as Dr Ian Kelson, a doctor from before the epidemic, living in isolation beside his creation: the Bone Temple itself, a sculptural monument to the dead. Kelson has a strange, almost spiritual mission. He reaches out to the infected and tries to bring back their humanity – as if the final act of medicine, in this world, is not cure but witness and recognition. Yet even he feels ambiguous, almost Colonel Kurtz-like: he’s smeared in sticky orange paint that makes him look demonic, as though he’s crossed into some ritual identity of his own.

What emerges is a film that’s less about jump-scare zombie mechanics than about the moral collapse, and moral reinvention, of human beings. Some of the infected, and some of the living too, carry broken shards of memory: flashes of the old Britain, even something as mundane as a railway carriage from the 1990s. They remember a different world, and the world they inhabit now is a patchwork imitation of what life used to be: families, routine, belonging, distorted into something desperate. The question becomes: can hope ever come back? Or is ‘hope’ just another story people tell themselves to survive one more day?

And then there’s a sequence so audacious it feels almost deranged: amid pageantry, fire, lighting effects and a pounding soundtrack, Kelson dances to Iron Maiden’s ‘Number of the Beast.’ It’s extraordinary – genuinely mind-blowing – and it crystallizes what the film is doing. It’s not just horror; it’s spectacle, ritual, ideology, the lure of violence dressed up as meaning.

In this instalment, the zombies almost take a backseat. The most unnerving figure isn’t simply the infected giant – the one who’s about six foot eight – but the sense that everyone is either relearning humanity, or regressing from it. ‘The Bone Temple’ keeps returning to that grim idea: the infected may rip people apart, but it’s the choices of the uninfected – the systems they build, the gods they invent, the cruelties they normalize – that feel truly beyond recovery.

Leave a comment