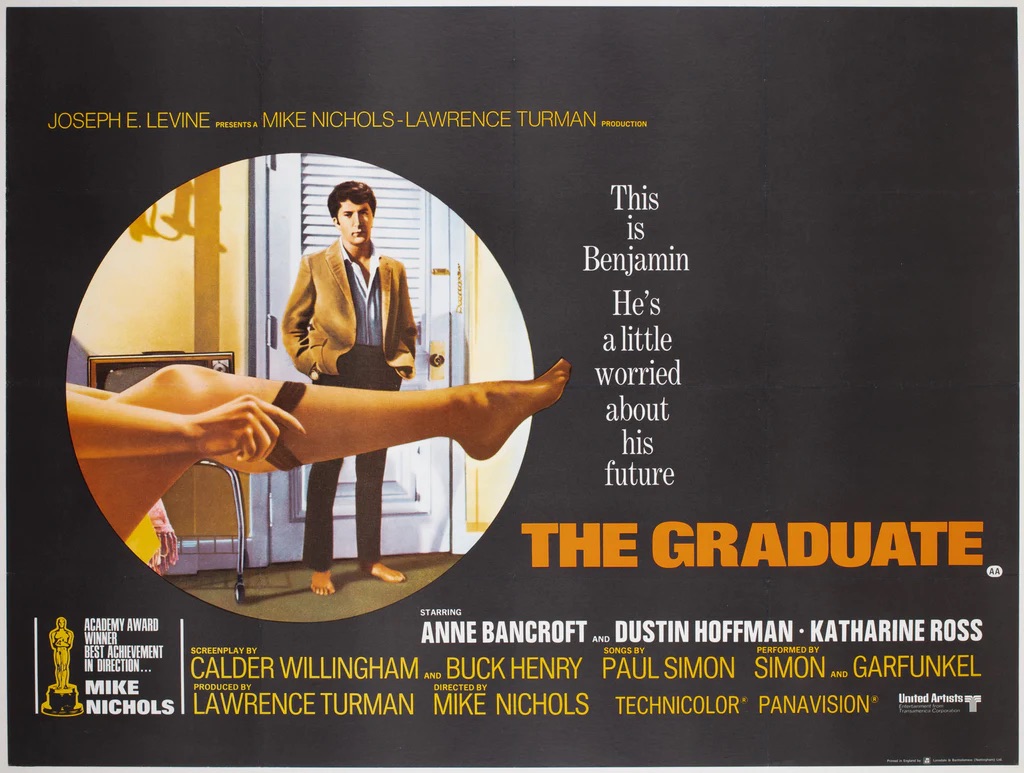

‘The Graduate’ was a risky, destabilizing film for its time. Directed by Mike Nichols, who won the Oscar for Best Director, it arrived in 1967 at a moment of profound cultural upheaval in America. Although the age difference between Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft was only around six years, the film constructs the eponymous Mrs. Robinson as a deeply unhappy married woman with an adult daughter, and Hoffman’s Benjamin Braddock as a newly graduated young man paralyzed by uncertainty.

Hoffman was about 30, playing someone fresh out of college and utterly directionless. His parents want him neatly folded into their world – job, marriage, continuity – and they actively encourage him to date Mrs Robinson’s daughter. The central irony, of course, is that Benjamin is already having an affair with Mrs. Robinson, who is violently opposed to that relationship. What begins as awkward farce curdles into something far more caustic and unsettling.

It’s often hard to pin down exactly what kind of film this is: black comedy, social satire, generational critique, or something more toxic. What’s fascinating is that the affair itself becomes a rite of passage. Through Mrs. Robinson, Benjamin acquires a veneer of sophistication and confidence – enough, ironically, to make him “suitable” for her daughter, Elaine (Katharine Ross). In that sense, she creates the man who then repulses her. She wanted the boy, not the person he becomes.

There is something undeniably predatory about Mrs. Robinson, which makes the film feel decades ahead of its time. The gender politics are uncomfortable, unresolved, and deliberately so. Benjamin’s parents want him to be an extension of themselves, but Benjamin instead becomes emblematic of a generational rupture – the uncertainty, drift, and rebellion of late-60s America.

The final act becomes almost a road movie, with Benjamin racing to stop a wedding that may already be too late. The closing scene famously refuses resolution: is this an act of liberation or panic? Is there a fairy-tale ending waiting, or simply another kind of uncertainty? And how differently would we read this story if the genders were reversed?

The opening image of Benjamin on the airport travelator at LAX – passive, carried forward without agency – says almost everything, an image later echoed decades on in the opening scene of ‘Jackie Brown’. ‘The Graduate’ ends as ambiguously as it begins: not with answers, but with a question about what freedom actually looks like once you’ve seized it.

Leave a comment